Bringing Down the Red Lines

Fall 2024

University of Virginia

This work was done as part of the Fall 2024 course Planning Theory and Practice. This poster will be presented at the 2025 Natural Hazards Workshop hosted in Denver, Colorado.

Across the country, the increased frequency, intensity, and duration of extreme heat waves in urban environments are the deadliest and most widely experienced consequence of climate change. Concentrated heat output intensified by urban surroundings is known as the urban heat island effect. The severity of extreme urban heat is not evenly distributed across a local urban environment. Many of the areas experiencing the most severe heat island effects coincide with the areas in which predominantly Black communities reside. These communities have been marginalized through histories of racist zoning policies, including through the practice of redlining. A 2020 study of 108 urban areas in the US by Hoffman et. al explicitly links these historical housing policies to the disparate impact of heat on residents in these urban areas, finding that “94% of studied areas display consistent city-scale patterns of elevated land surface temperatures in formerly redlined areas relative to their nonredlined neighbors by as much as 7°C.” Here, we compare three case studies in urban heat island mitigation.

I performed the layout of the poster, in addition to creating all graphical elements on the poster. The full poster pdf can be found here.

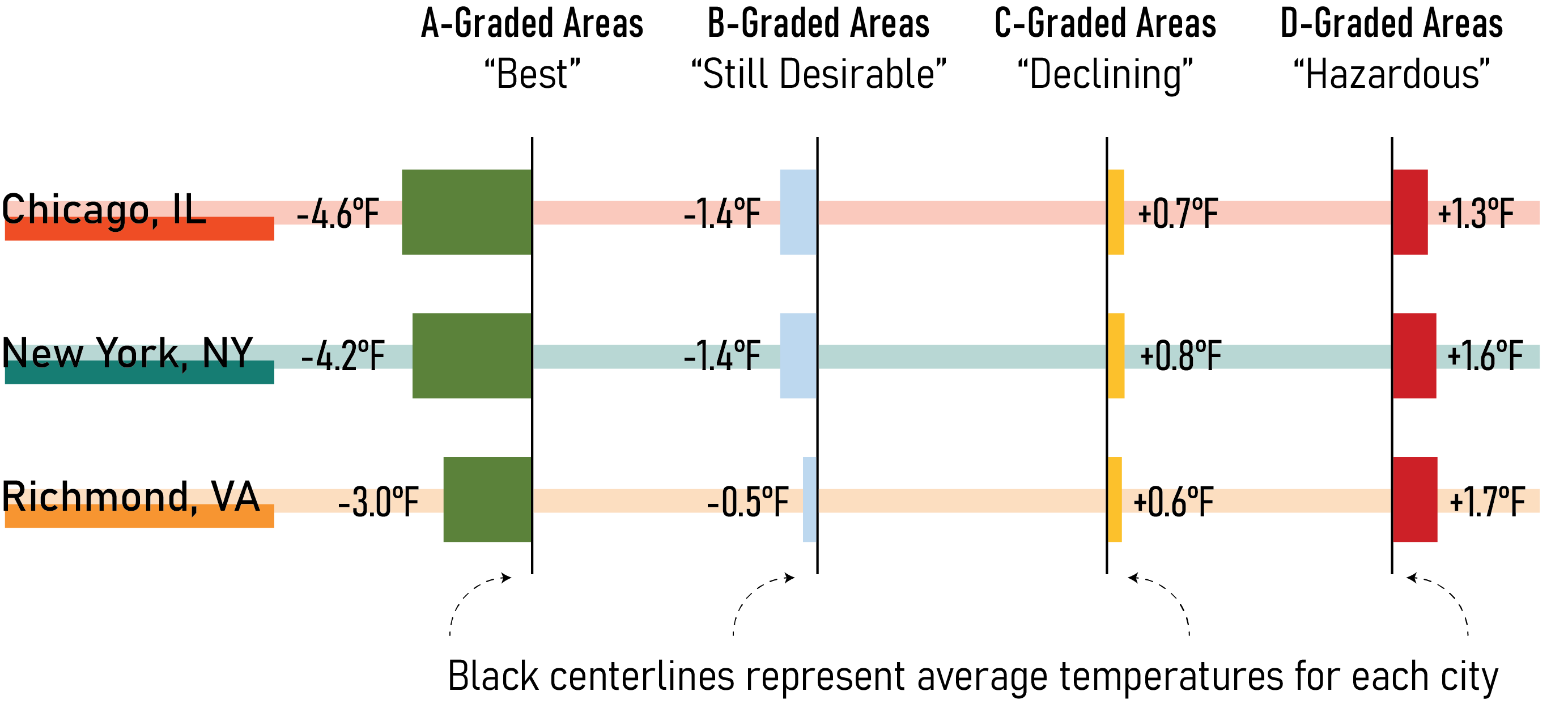

The chart above shows how average temperatures today compare to the city average across areas that were given different HOLC ratings from the 1930s redlining maps in each of the three cities from the case study. This table uses data from a NYT published data visualization. “D-graded areas” correspond to redlined areas.

The table below summarizes our comparisons across the three case studies:

While each of the three frameworks centers important planning considerations, we found that our emergent strategy case study was most effective at implementing tangible actions. The reparative planning case study centered necessary histories of injustice, but did not have a commitment to implementation. Our Just Transition case study charted out paths towards a vision of the future, but lacked a foundation of action and energy from the community in the present. Emergent strategies inherently emerge from community members are built upon their strengths and perspectives. Borne of collective histories, these present actions mobilize towards a collective future.